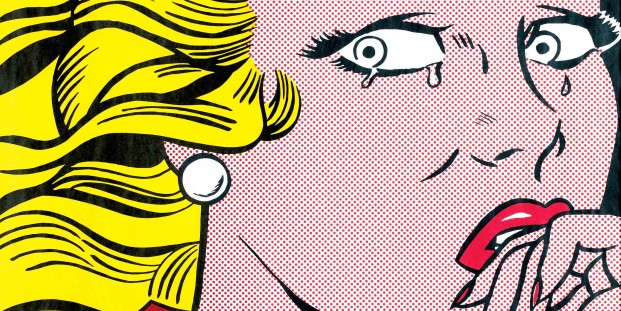

Aujourd’hui Roy Lichtenstein est considéré comme l’une des « stars »

du mouvement pop autant que comme un grand maître de la peinture américaine.

L’exposition dévoile l’ampleur, parfois surprenante, d’un artiste qui fut, dès l’origine, plus qu’un peintre pop : un expérimentateur de matériaux, un inventeur d’icônes, un amateur érudit de la peinture moderne.

Quatrième étape de cette exposition-événement organisée par le Centre Pompidou, en collaboration avec l’Art Institute de Chicago et la Tate à Londres, et également présentée à Washington, la rétrospective parisienne montre l’incroyable inventivité technique de Roy Lichtenstein à travers un corpus inédit de sculptures, de gravures, d’émaux, de céramiques…

Ces expérimentations plastiques, aspect méconnu de son travail, témoignent d’une recherche qu’il mena tout au long de sa carrière. Cette présentation bénéficie d’un soutien exceptionnel de l’Estate de Roy Lichtenstein à New York.

Today Roy Lichtenstein is regarded as one of the stars of the pop art movement as well as a great master of American painting. And yet, having been at the avant-garde of pop art for several years, Lichtenstein went much further.

As soon as he began to reference artists and styles from art history in his works, he was very quickly perceived as a postmodern artist. Then, in the last years of his life, returning to the classic genres of the nude and the landscape, he became almost a traditional painter. So that Roy Lichtenstein is, today, a “classic” artist. Yet the power of his art is also an amused distance, critical without becoming cynical, that he applied to both himself and to art, from early on to the end of his life, the importance of which must be recognised. In one of his last interviews, Lichtenstein did not deny the interviewer's first question: “Are you sure that you have never created a work completely devoid of all trace of malice, humour or irony?”

“What can you paint that's not completely ridiculous?” he exclaimed as early as 1972, before bursting out laughing, in the middle of a serious interview about the series of still life paintings he was in the midst of producing. Still lifes inspired by the works of great modern masters. Matisse, Picasso, Léger, Le Corbusier, etc. are referenced or evoked in a title which mentions, if not their name, then the appropriate movement: Cubism for some, Purism for others. In 1972, at the age of 49, Lichtenstein had already been identified as one of the leading lights of the pop art movement for ten years, even though he was unveiling a series of paintings whose references to art history would make him one of the first “postmodern” artists.

The Centre Pompidou today presents a retrospective of his work, featuring a selection of 124 paintings, sculptures and prints that shed an original light on his career. The exhibition reveals the often surprising depth of an artist who was, from the beginning, more than just a pop painter. He was an experimenter of materials, an inventor of icons and an educated connoisseur of modern painting.

As the fourth stop of this exhibition event organised by the Centre Pompidou, in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago and the Tate in London, (and also shown in Washington), the Parisian retrospective shows the incredible technical inventiveness of Roy Lichtenstein through a body of original sculptures, prints, enamels and ceramics. These experimentations, a little known aspect of his work, demonstrate the research he undertook throughout his career. This exhibition has enjoyed exceptional support from the Estate of Roy Lichtenstein in New York.

It all began in 1962. At the same time as he was producing the enlargements of extracts from comic books and consumer goods, begun in 1961 and which are some of his most well-known works – so well-known that they conceal the rest, which this exhibition attempts to rectify –, Roy Lichtenstein began to create paintings which spoke about the history of painting.

Contrary to popular belief, the two series developed at the same time, although the comics dominated until the middle of the 1960s. Pop art and postmodernism coexisted. His reinterpretation of modern art history began with a series of portraits inspired by Picasso, then paintings referencing Mondrian and Cézanne, for which he had to endure harsh criticism of plagiarism from certain American art critics.

In the middle of the 1960s, Lichtenstein began a series of paintings, mostly abstract, which provided a reinterpretation of geometric, repetitive and machinist shapes, typical of Art Deco and the “modern style”. “What interests me about the art of the 1930s is that it is conceptual. It obeys a senseless logic based on the compass, the set square and the triangle. I also believe it was the first time in history that people were so concerned with being modern […] their art presents a naïve and confident sophistication which pleases me.”

In 1977, the Centre Pompidou acquired Modular Paintings with Four Panels #4 (1969), a work composed of four paintings with an identical motif: once assembled side by side, they form one large painting, which is potentially infinitely extendible.

From 1965 and for several years, Lichtenstein worked on the recurring motif of an enlarged and simplified brushstroke. This metaphor of painting is also a quite unapologetic nod from the painter to abstract expressionism, another of those styles which had become historic at the time when he painted his Brushstrokes and which he therefore had to simultaneously salute, fight… and surpass by “copying” whilst modifying the “clichéd” image.

These “readymades” of different well-known 20th-century styles and artists were successively addressed by Lichtenstein, not systematically, but depending on his admiration, exhibition visits and incessant revisions. He applied this approach simultaneously in painting, sculpture and print.

After the Cubist still lifes between 1973 and 1975, there were works inspired by Futurism between 1974 and 1976, while references to Purism dominated from 1975.

Between 1977 and 1979, he explored Surrealism, and finally German Expressionism between 1979 and 1980.

He was probably one of the first artists to turn this double-edged look at art, combining respect for the artist whom he appropriated and criticism of a new economy which transformed art works, as objects of everyday use, into consumer objects, into the main focus of his work: both postmodern and “appropriationist”. Yet Lichtenstein applied this mise en abyme to his own work very early on.

In 1972, whilst highlighting art's lack of seriousness, he included his own paintings in the background of still lifes, thus making reference to modern masters. One year later, in 1973, he began work on the large Artists' Studios, in which were gathered, aside from references to Matisse, accurate copies of his own existing paintings and even sketches of future works.

In the 1980s, the references to both art history and his own work doubled, often literally: whereas the Two Paintings (1983-1984) make two paintings and two styles coexist in the same frame, the Reflections (1988-1993) put under glass a reproduction blurred by reflections - either paintings by modern masters or his own pop works - some of which were actually painted and others not. Lichtenstein always retains an amused eye on the process of copying and reproduction that is at work in his art.

The most striking example – based around which the Paris retrospective is organised – is an important body of frequently overlooked sculptures.

This exhibition highlights these both three-dimensional and relatively flat works, where the trompe-l'oeil effect is often startling.

They span all the movements and styles explored by the artist as a painter: he depicts the various heads with a graphic line drawn in the space and primary colours whatever the style (Expressionist, Surrealist, Archaic…).

In the middle of the 1990s, Lichtenstein, then in his seventies, tackled a new area in the history of art: the landscapes of ancient China, in the style of the Taoist philosophy, which conceived the figure of the artist as a philosophical sage whose practice of painting encouraged longevity. The painter's last parody, at the twilight of his life.

Pop Humour. In spite of his rapid success, Roy Lichtenstein did not take himself very seriously. He cast an amused eye on both his work and himself, as shown by the photographs taken by Ugo Mulas in 1964-1965.

He himself placed the source of this humour, which was both a character trait and a stylistic particularity of his work, in modern art, among the artists from whom he would very early on appropriate motifs and/or style.

It was precisely these modern masters who were, so he believed, the first to integrate humour into art. Humour is at the heart of Lichtenstein's work: he would even consider it as one of his rare personal inventions, as well as a defining trait of pop art.

A photographer since 1954 at the Venice Biennale, Ugo Mulas witnessed the emergence of American artists on the international art scene in 1964. That year, Robert Rauschenberg was awarded the Grand Prize for Painting and the art critic Alan Solomon presented works by the artists Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg in the American section.

The Italian photographer, who met the New York gallery owner Leo Castelli, Solomon and most of the exhibited American artists on this occasion, went to New York to capture this breath of fresh air in the art world.

For his famous New York work, The New Art Scene, he photographed Lichtenstein many times: in his studio, working and in a surprising collection of photographs where the artist play acts, using his works as accessories in a real pop photo-novel.

Artists' Studios Between 1973 and 1974, Roy Lichtenstein painted four monumental canvases showing painters' studios crammed with paintings and brushes. These Artists' Studios were inspired by the composition of Atelier Rouge (1911) by Matisse and used some of his motifs: the philodendron, fruits, the carafe and of course the famous Danse (1909), which appears in the background of one painting, to which it gives its name: Artist's Studio “The Dance” (1974).

These paintings form above all a catalogue of works by Lichtenstein. On the walls of the studios are reproduced, in miniature and with great accuracy, his own paintings, such as Look Mickey (1961), the inaugural painting of the pop period, and certain objects, which furnish the four interiors, themselves take on subjects treated before in isolation. For example, the canapé or the telephone in Artist's Studio No. 1 (Look Mickey) (1973) appeared respectively in an ink drawing of 1961 and a canvas painting of 1962.

Lichtenstein the printer . Although Lichtenstein did produce prints from the end of the 1940s, this practice intensified from 1969 with the creation of Cathedrals and Haystacks after Monet, whose seriality of motif particularly lent itself to multiple production.

From this date, he produced a new series almost every year, spending several weeks developing the proofs with master printers. He worked with reputed studios for their outstanding expertise and their involvement in research into technical innovations.

An insatiable creator, Lichtenstein often combined several techniques in the same image (screen printing, lithography, etching, woodcut, embossing, etc.) and used all kinds of media (papers, plastic or metallic sheets, etc.). During the 1960s, he frequently used Rowlux, a translucent and shimmery plastic film, whose changing nature according to the light offered unusual kinetic properties.

Curator: Camille Morineau

Exhibition sponsored by the London Tate Gallery and the Art Institute of Chicago

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario